Phenology

![]()

Observations

![]()

I settled in the USA in 1974. Having grown up in India, it was a major change. There was a lot to assimilate in a new country with a different culture, and it was overwhelming. I focused on graduate school and then slowly began to adjust to the lifestyle, climate, and surroundings.

One day, when I parked my car in the university parking lot, I saw a small flock of bright red birds on the ground. I described these birds to a fellow graduate student, wanting to know what these were. He was amused, "You have never seen a cardinal?" I was irritated by his condescending tone. My advisor was standing nearby and overheard this exchange. He was an avid birder and encouraged me to learn about the birds in the area. When I graduated, he gave me two bird field guides (Peterson and Golden series).

In the summer of 1980, when I was working in Delaware, I took a course in birding. I was introduced to many birds I had never seen before. We were given a printed checklist to note the species we saw. The course was interesting, but I did not enjoy the field trips as much. We were keeping count of the species we saw without knowing much about their behaviors.

The next fifteen years were busy with my occupation as a research scientist in the field of applied physics. It was not until I moved to Long Island, New York in 1992 that I started observing the birds in my backyard on a regular basis. I was fascinated by the migratory birds and found that they arrived within the same week each year. I read several books on migration but the explanations of how birds navigate were not satisfactory.

In 1997, I moved to upstate New York. I chose a site with a wooded backyard for building my house. I could look at the top of the trees and see birds even before I got out of bed. Landscaping and planting trees and shrubs took a fair amount of time. I took courses in landscaping and learned about native plants that attract wildlife, birds, and butterflies. My professional life was demanding, but I kept a notebook and recorded the birds I saw through my kitchen window.

After retirement, I joined the local bird club in 2018 and started going on field trips with other members of the club. With help from other experienced birders, I have been learning to spot and identify birds by shape, size, color patterns, call and flight. I have more time at home to watch birds and other wildlife. I keep binoculars handy near several windows looking out in different directions. Cameras with long telephoto lenses to photograph and a spotting scope to see birds perched further away extend the range of observations.

Although eBird from Cornell Lab of Ornithology is very popular with birders all over the world, I wanted to record all wildlife in and around my yard and keep track of the impact of habitat on different species. Our team member Hemant Sogani, who resides in India, has designed a database (AAP Application) to track these observations and continues to enhance it. I record only when I can positively identify a species by sight or call. My skills in identifying birds and some insects have been improving over time, but there is a lot that I miss.

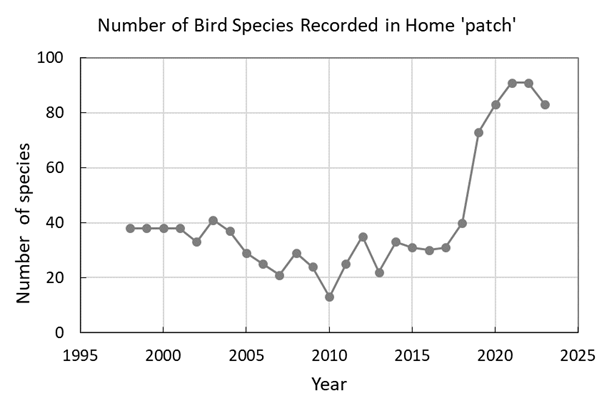

Fig. 1 shows the number of species recorded in my Home 'patch' from 1998 through 2023. In the first four years, 38 species were recorded each year. In the following years, I was mostly noting the arrival dates of migratory birds, and the number of species sighted in a year varied with the effort. A steep rise in the number of species occurred after 2018 as my bird identification skills improved and the sightings were noted on a daily basis. This increase is primarily a result of rare and uncommon birds which I had previously missed. The species count saturated at 91; the decline in 2023 to 83 species is mainly because many of the migratory species passing through this area in spring used a more westerly route to avoid rainstorms.

Fig. 1. Number of species sighted in each year from 1998 to 2023.

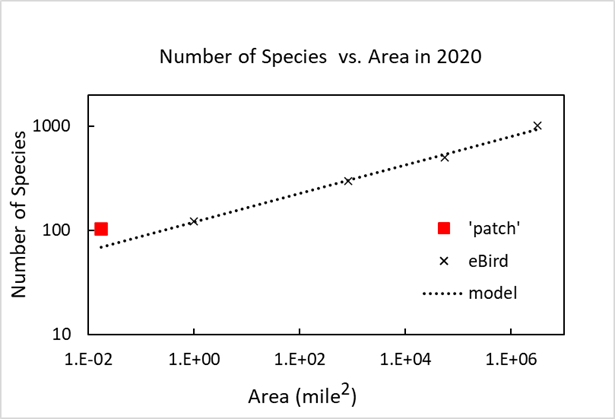

The number of observed species increases with area. We used data logged in eBird through the summer of 2020 to generate a relationship between number of species and area. An eBird hotspot close to the Home 'patch' Dutchess Rail Trail--Hopewell Depot to Lake Walton Road, was selected to get species count with many observers. The areas and number of observers are progressively larger for Dutchess County, New York State and the lower 48 states in the USA. The data are listed in Table 1, plotted on a log-log scale in Fig. 2 and fitted to build a model equation:

![]()

where XSP is the number of species and OA is the observation area.

Table 1. Area, number of observers and species count from eBird listings in 2020.

| Location |

Area (square miles) |

Number of observers |

Species count |

| 1.0 |

94 |

123 |

|

| 825 |

2315 |

299 |

|

54556 |

45000 |

500 |

|

3,120,428 |

484600 |

1013 |

Fig.2 (a). Number of species vs. observation area log-log plot.

Fig.2 (b). Number of species vs. observation area linear-log plot plot.

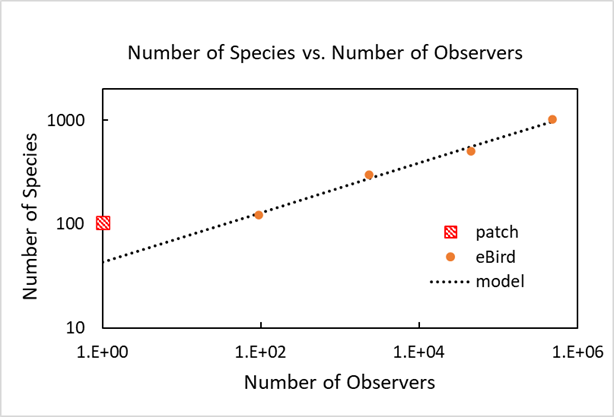

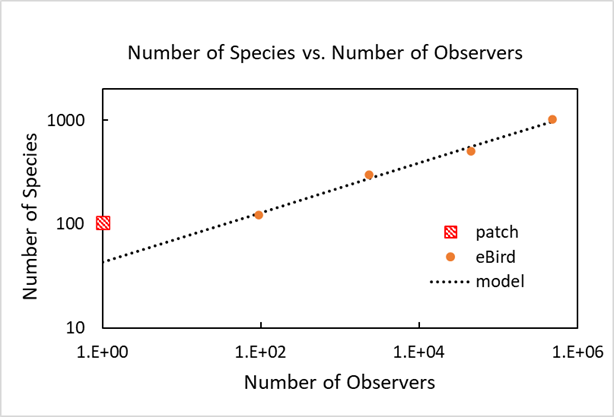

In the eBird data, observer skill and motivation are unknown but important factors. Some observers may record all birds seen, and some may record only uncommon birds. In Fig. 3, number of species is plotted vs. number of observers from eBird data in Table 1. The species count appears to increase with the number of observers which is in turn related to increase in observation area. The data are fitted to get the model equation:

![]()

where XSP is the number of species and XO is number of observers.

The estimated viewing area for the Home 'patch' is 0.017 square miles, and sightings are recorded by only one observer. Using the model Eq. [1], the projected number of species in the Home 'patch' is 69. From Eq. 1 and Eq. 2, it would take seven observers in the Home 'patch' to record 69 species.

The number of species in the 'patch' is 104 recorded by one observer. This indicates that the observation time and observer skill in the 'patch', hence the net effort, is larger than average survey effort reported in eBird.

Some reasons for higher than predicted number of observations are:

1) daily observations for improved better coverage

2) large perimeter-to-area ratio and overlap between neighboring areas.

Fig. 3. Number of species vs. number of observers from eBird data in Table 1.

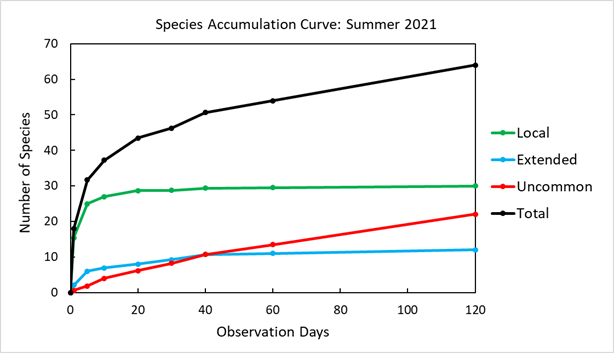

We used the 'patch' data in the AAP tool to generate a species accumulation curve which describes the number of species reported as a function of observer effort. Since there is only one observer for the 'patch', survey effort is measured as the number of observation days. The data are listed in Table 2 and plotted in Fig. 4 for the observations in the summer of 2021 (May 7 to September 8). The number of calendar days for this period is 125 and only 5 days were missed.

The procedure for generating the plot is described below:

1) Around the middle of summer, the days on which observations are made are grouped into blocks of 1, 5, 10, 20, 30, 40, 60 and 120 days. This ensures that each block has the desired number of observation days.

2) Avian species are separated into local, extended, and uncommon categories based on the probability of sighting as described in Avian Sightings.

3) Number of species sighted in each of the categories is computed as the mean sighting in each block and plotted as a function of number of days in the blocks.

Table 2. Mean sightings of local, extended, and uncommon species over different number of days in the summer of 2021 (May 7 to September 8).

| Observation days |

Local species |

Extended species |

Uncommon species |

Total species |

| 0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

15 |

2 |

1 |

18 |

| 5 |

25 |

6 |

2 |

32 |

| 10 |

27 |

7 |

4 |

37 |

| 20 |

29 |

8 |

6 |

44 |

| 30 |

29 |

9 |

8 |

46 |

| 40 |

29 |

11 |

11 |

51 |

| 60 |

30 |

11 |

14 |

54 |

| 120 |

30 |

12 |

22 |

64 |

Fig. 4. Number of species sighted as a function of observation days.

From this data, we estimate minimum number of observation days required for sighting 90% of species in each category. As expected, the number of days is five for local species, 30 for extended species, and the count of uncommon species continues to increase even after 60 observation days.

The above findings are consistent with Fig. 1 which shows the sharp increase in the number of species after 2018 as the observer effort and skill improved. However, observations made once a week or so will give a fair assessment of the species in the area for tracking habitat changes.

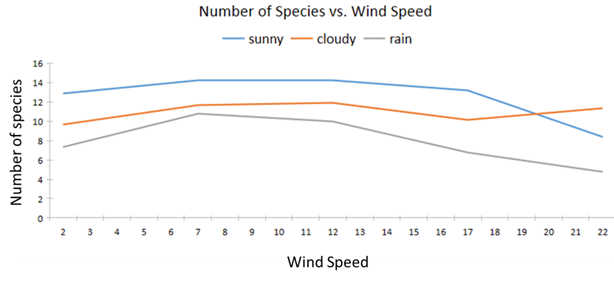

Table 3 shows the average species sightings under different weather conditions. Data support the general idea of choosing a sunny day for surveying an area. As all birders know, morning is the best time to view most bird species.

We also record the wind speed and direction around sunrise. Wind speeds and direction may change during the day. Hence, it is difficult to correlate wind speed with number of sightings. Average number of species observed under different sky conditions and wind speed are plotted in Fig. 5. This illustrates that in general, high winds and heavy rain do impact bird movements and sightings.

Table 3. Species count in AM under different weather conditions.

| Weather Condition |

Average species count |

Number of days (AM) |

Sunny |

13 |

421 |

Cloudy |

10 |

311 |

Rain |

8 |

91 |

Snow |

5 |

17 |

Fog |

9 |

8 |

Fig. 5. Average number of species observed vs. speed under different sky conditions.

Our method of counting bird species in the Home 'patch' gives us a good representation of the bird population in this small area. Year to year variations in the population and impact of habitat and weather fluctuations are detected and being analyzed.

| Symbol | Description | Units/Limits |

| XSP | Number of observed species | None |

| OA | Area of observation | None |

| XA | Number of observers | None |