Phenology

![]()

Observations

![]()

I came to know of a nesting pair of Bald Eagles in a park by the Hudson River from a birding enthusiast. It was easy to locate the nest in this 300-acre park; there was a photographer with a camera on a tripod positioned to point at the nest. Nests of large birds of prey and some waterfowl that begin nesting before the leaves emerge are often easy to observe once the location is known. Nests of songbirds are small and usually challenging to find. Some birds build nests in partial view, but most nests are hidden away.

From pair bonding and nest building to incubation and raising young, the activities during the breeding season teach us species survival strategies in the wild. I have been tracking these activities in the Home 'patch' for over twenty years. Some of the earlier records (2000 to 2018) have limited observations, but more detailed descriptions since 2019 are entered in the AAP Application. There are no bird feeders and nest boxes in my Home 'patch'or nearby, maintaining a natural environment in this suburban habitat bordering a nature preserve.

In the last five years (2019-2023) I have located and observed nests of American Robins, Carolina Wrens, Chipping Sparrows, House Finches, Northern Cardinals, Red-tailed Hawks and Ruby-throated Hummingbirds in the Home 'patch'. Many other species were seen collecting nesting material or carrying food to nestlings. A few additional species of recently fledged young and adults feeding young were also seen. Following the guidelines of New York State Breeding Bird Atlas a total of 30 species have been 'confirmed' breeding in the 'patch' and surrounding area. These avian species have been adapting well to changes in the habitat and encroachment of man-made structures and landscapes.

Here we describe the nesting behaviors of seven species whose nests were located within the Home 'patch'. The locations of their nests are indicated in the picture below. American Robins and House Finches built nests on the exterior structure of my house. Carolina Wrens selected an equipment housing situated along the wall of the house. Chipping Sparrows and Northern Cardinals nested in shrubs close to the house. Red-tailed Hawks nested in the adjacent woods, and Ruby-throated Hummingbirds stayed safely up in a tall tree.

Nests of three other avian species were found in years prior to 2019. Downy Woodpeckers nested in a dead tree in the woods in 2000, and Mourning Doves in a large shrub next to the house in 2006. In 2012 a pair of Northern Mockingbirds were nesting in a shrub next to the foundation wall of the house. The fascinating story of a mockingbird with the ability to recognize humans near its nest is posted on this website - 'Mockingbird's Wrath'

Techniques for observing a nest varied with location - sometimes viewing at close range was possible, and sometimes only the movements and action of adults could be noted. Following our non-intrusive approach to investigating wildlife, we took care not to touch any birds, chicks, eggs, or active nests. American Robins have nested on the support pillar of the deck at the back of my house since 2001. In this location the nest was visible at close range through the spacing between deck floorboards, providing an opportunity to observe activities without disturbing the inhabitants. House Finches attempted to nest on a segment of gutter for three years but lost the chicks to predators each time. Carolina Wrens found it safe to nest under the lid of a propane tank. The nests of Chipping Sparrows and Northern Cardinals were in dense shrubs and once discovered were checked only periodically. Red-tailed Hawk nests were high up on trees and could only be viewed from a distance. Although the Ruby-throated Hummingbird's nest in 2022 was very high up, it was visible through a window of the house. With a spotting scope pointed at the nest, the movements of the mother and the nestlings were carefully recorded from nest building to the time the chicks fledged.

The 25 nests observed each year since 2019 are listed in Table 1 ; 'green' indicates success and 'red' indicates failure.

Table 1. Number of nests located and observed.| Species |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

|

| 1 |

American Robin |

3 |

1 + 1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

| 2 |

Carolina Wren |

|

|

|

|

1 |

| 3 |

Chipping Sparrow |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

| 4 |

House Finch |

|

1 |

1 |

2 |

|

| 5 |

Northern Cardinal |

|

|

|

|

2 |

| 6 |

Red-tailed Hawk |

1 |

1 |

|

|

|

| 7 |

Ruby-throated Hummingbird |

|

|

|

1 |

|

Whenever possible we noted the behavior of birds from arrival in spring, pair bonding, nest building and raising young to post-nesting activities in preparation for migration or settling down here for the winter. Observing how individual birds cope with weather fluctuations, food availability, predation, clutch size variations and brood parasites has been fascinating. Nature has equipped these creatures with the 'tools and technology' to survive and to thrive under favorable circumstances.

Common birds in the summer, American Robins are often seen on grassy areas in housing developments and parks. Male and female are similar with rufous breast, brown upperparts, dark head, and a yellow beak. By careful examination, the male can be distinguished from the female by his deeper orange breast and more conspicuous streaking on the throat. Most of the population migrates south in the winter, returning by mid-March. Nesting begins in mid-April and ends in August/September, producing up to three broods in a season.

In the last twenty years I have located 25 robin nests in the Home patch. Their favorite nest site has been on top of the wood support post of my deck. Six feet above ground and sheltered by the floorboards of the deck, it is a safe place to raise young. The post is centered on a 1/4 inch spacing between the floorboards. By kneeling on the deck floor and looking through the narrow spacing, I got a top view of the nest at close range. In 2015 when I showed it to Lawrence Slomer, he suggested that the small objective of a smartphone camera would be perfect for taking pictures and videos of the nest through the gap. This trick worked until the chicks were about a week old, and then all I could see from the top was a pile of feathers and beaks. A second viewing port was through the basement window, providing a sideview of the nest. From there I watched the open beaks of the chicks above the nest rim and the adults bringing food and performing housecleaning duties. With a camera mounted on a tripod on the windowsill, I took pictures and videos.

The deck site was used in most years for the first one or two broods. Later nests were higher up in deciduous trees and difficult to view. In 2022 and 2023 robins abandoned the deck site and used shrubs and/or vines with dense foliage for nesting. These nests were three to four feet above ground and checked once every three or four days. Images of the nests were obtained with a smartphone camera held above the nest to get egg and chick counts.

In 2021 we placed a HD webcam equipped with a motion detector (HD Bird Camera Kit from Green Backyard) on the sidewall of the deck close to the nest. The 2.5 mm wide angle lens of camera has a viewing angle of 120o, and although designed to be installed in a bird box, it worked well for this nest site. The camera housing was mounted on the sidewall of the deck, 20 inches from the center of the nest and protected from rain by a small housing. The camera, powered by a cable connection to a wall outlet, provided color images during the day and sharp black-and-white images at night using invisible infrared LEDs. With the aid of an antenna on the camera housing, images were transmitted to a smartphone via my home Wi-Fi network.

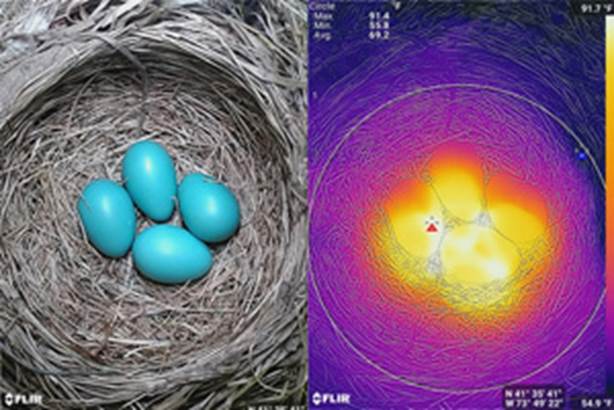

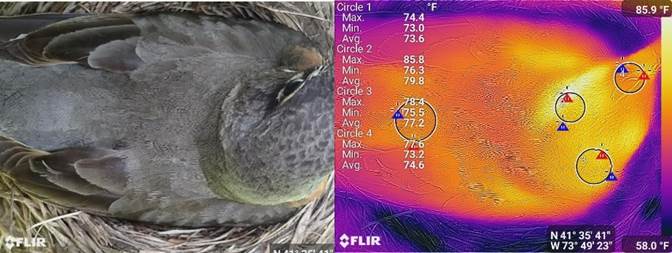

FLIR (Forward Looking Infra-red) thermal images of the nest were captured using a CAT S61 smartphone (also suggested by Lawrence Slomer) placed above the gap between the floorboards. To get a clear view of the nest, the gap was made wider along the thickness of the board. This increased the viewing angle without affecting the spacing on top, an important consideration for minimizing the nest's exposure to rain. Maximum and minimum temperatures of the eggs were determined using the MyFLIR App on the smartphone with point measurements. Ambient temperature was measured just outside the nest rim. The camera also displayed an optical image which was slightly displaced from the thermal image due to the different positions of the two camera lenses.

The different nesting stages, from building a nest to fledglings off the nest, are described in the following sections. Although there is much commonality among the nests observed there is always something unique about each nest. We have tried to include both, to bring out the adaptability of these birds and their young ones.

Nest Building on Deck Support Post: A female robin brought long strips of dry grass to the nesting site and arranged them in a circle. Thin twigs and dry grass were used to build the walls of the nest. Sometimes if it was the first nest of the season, she threw the collected material on the ground and started again. Once the walls were defined, she brought wet mud and placed it at the base. Then she sat in the center and rotated using her feet to pack the mud on the base and to strengthen the walls. When the mud dried, one could see the rings formed by her circular motion. Next, she layered the base and the walls with finer dry grass. The nest building process illustrated in the photographs below was for the first nest of season in 2021 and took five days to complete. In 2016 the first nest took one week to complete. In 2015 the second nest under the deck was completed in one day - perhaps by an experienced female eager to lay eggs!

The nests were circular with an inner diameter of about four inches and an inner depth of about two inches, the interior custom shaped to her body size. They were solidly built and stayed intact the rest of the season. However, we did not witness the reuse of a nest. When we removed the nest under the deck after fledging in 2015, a new nest was constructed in the same place. If we did not remove a used nest, it was not occupied again.

Nest progression Day 1

Day 2

Day 3

Day 5

American Robin collecting nesting material

Dried mud on the base of the nest

The male robin stayed with the female while she was building the nest. Sometimes he accompanied her from the area where she was collecting nesting material and waited on a nearby tree for her to make another trip. In some years, there were two pairs of robins building nests at the same time, one under my deck and another under a neighbor's deck. The two males defended the imaginary borders of their territories and kept each other away from their chosen partners.

Egg Laying: The first egg was laid one to five days after the nest was completed. The large variation is partly because the nest completion day was difficult to judge. The female laid one egg every 24 hours, typically between 10 AM and 2 PM. She was on the nest for about two hours during egg laying. The blue colored oval shaped eggs with one pointed end were about 1.25 inches long. Of the 23 nests observed with eggs, 12 nests had four eggs, 10 had three eggs and one nest had two eggs. Incubation began after two or three eggs were laid.

Incubation: As in the case of most songbirds, incubation was done by the female. She had the challenging task of keeping the eggs warm. In early spring when the ambient temperature can drop below freezing, she must sit on the nest with only brief excursions for foraging. On warmer days, she may be away for longer periods during the day. In 2021, with the aid of a thermal imaging camera and the webcam, we observed the behavior during incubation more closely.

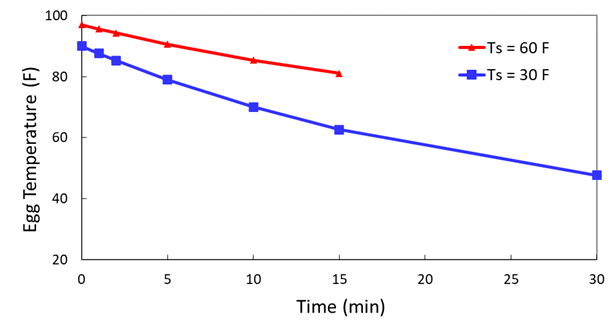

Thermal images were taken just after the robin left the nest and at intervals of one minute for the first five minutes and five minutes thereafter. The plot below shows the egg temperature on two different days with ambient temperatures of 30 oF and 60 oF. The eggs were at ~ 95 oF when the mother left the nest. On a typical day at the end of April, the cooling rate of the eggs was ~ 1 oF/minute when the ambient temperature was 55 oF. She could be away for 15 minutes or so while the eggs remained above 80 oF. On one colder day there was repair work in progress under the deck, and the mother robin chose to stay away for 30 minutes. It was a choice between the perceived exposure to danger from the serviceman and survival of the eggs. Both the male and female stayed on a nearby tree calling softly but did not approach the nest. The egg temperature had dropped to 50 oF before she returned and may have caused some damage. From the egg temperature vs. time plot, she needed to be back within five minutes to keep the eggs above 80 oF.

Optical and thermal images of robin eggs

Egg temperature as a function of time with ambient temperatures Ts at 60 oF (red), 30 oF (blue)

The optical and thermal images below show the robin on the nest and her surface temperature. Her head temperature was ~ 80 oF and the beak and the back were at ~ 75 oF. The nest was large enough to accommodate her body with the head and tail sticking out (nest inner diameter = 4 inches, robin length from beak tip to tail end = 10 inches). She maintained the eggs at ~ 100 oF by keeping them close to the brood patch, an area of bare skin on her belly that loses its feathers during incubation. The body temperatures of birds are in the 102 oF to 109 oF range, considerably higher than normal human body temperature.

Optical and thermal images of robin on her nest

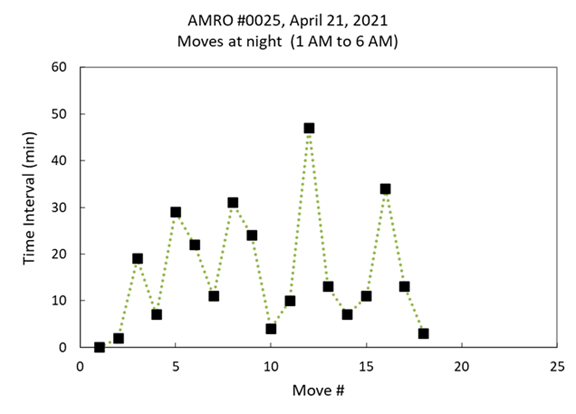

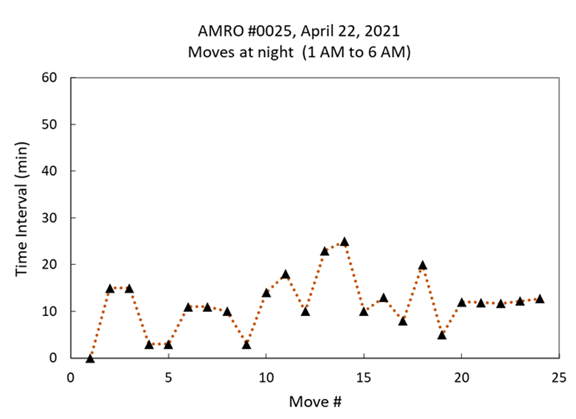

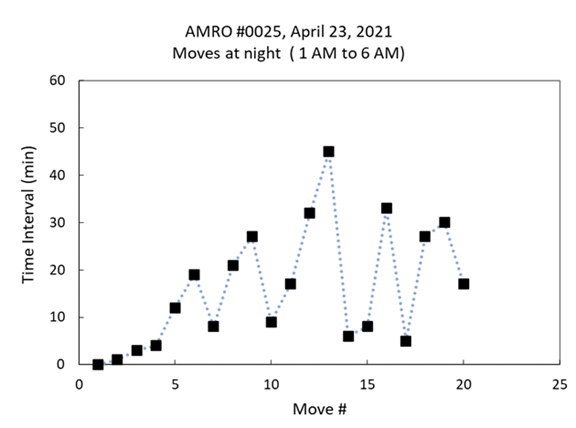

As we can see in the thermal image, all eggs were kept uniformly warm. The mother must shuffle the eggs at regular intervals to maintain uniformity. The webcam captured a 10 second video each time the robin shifted her position. We could witness the shuffling of eggs all night long. The four plots show the intervals at which the robin shifted the eggs between 1 AM and 6 AM on four different nights. The average interval between moves was about 15 minutes, spaced more evenly on April 22nd which was the coldest night. On other nights, she alternated between long and short intervals. She was vigilant all hours of day and night!

Female robin: time intervals between moves between 1 AM and 6 AM during incubation

While the female robin was busy incubating, the male perched on nearby trees performing guard duty. He began singing at pre-dawn, about 50 minutes before sunrise each day, and continued throughout the day. His internal clock was well tuned to sunrise (see Dawn Chorus in the Home 'patch'). Periodically he visited the female on the nest. In the following photographs the first image shows the female on the nest. In the second image the male is perched on the post, and she is talking to him. On another occasion, the male came to the nest while the female was away. He sat on the post next to the nest and then inspected the nest by getting on to the rim. He then left and the female returned within five minutes and resumed her duty.

Female robin on nest

Male listening to the female on nest

Male robin visiting and inspecting the nest while the female is away

Brooding, Feeding and Fledging The eggs hatched 12 to 16 days after the last egg was laid. Although most of the time all eggs hatched on the same day, sometimes the process took over a day. As the eggs hatched, the eggshells were removed from the nest. In one nest (AMRO011) one of the four eggs did not hatch. Surprisingly the unhatched egg was intact in the nest all along and detected only after the three chicks had fledged.

The following photographs show the growth sequence in a nest with four chicks (AMRO022). The hatchlings are born naked and need help with thermal regulation. In the first few days, the mother spent a fair amount of time on the nest brooding the chicks, providing heat until feathers covered their bare skin. The chicks grew rapidly, and after one week feathers completely covered their skin. She was also very alert to weather conditions and protected the chicks from rain when the water dripped through the gap between the floorboards (Day 10 Photo).

Both the male and the female brought food for the chicks. The first brood in early spring grew on a diet of worms and insects. In July and August, berries were also part of the diet. One afternoon I noted that the adults brought food nine times in an hour to three five-day old chicks.

Day 1

Day 4

Day 7

Day 9

Day 9

Day 10

Day 10 (mother's protectionfrom rain)

Day 10 (father ready to catch fecal sac

Day 12

Day 14 (ready to fledge)

Fledging: The chicks grew and were nearly adult size before fledging, 12 to 16 days after hatching. They stacked their bodies with heads and beaks separated to receive food while managing to stay inside the nest in which even a single adult robin could not completely fit. Any chirping noise made by the chicks was not audible. All chicks received food, not necessarily at the same time. There seemed to be harmony in the family. In one nest mentioned earlier (AMRO011) where one of the four eggs did not hatch, the three chicks grew at different rates. One chick fledged on June 21st, the second on June 22nd and the third stayed for two more days fledging on June 24th. The adults adjusted food delivery based on the number of chicks in the nest. They were attending to the chicks that had fledged and the remaining one in the nest at the same time./p>

The number of days between nest completion and first egg laid (days to egg laying), between the last egg laid and all hatched (days to hatch), and between all eggs hatched and all chicks fledged (days to fledge) are listed in Table 2 for 11 nests for which data are available. Note that the time when a nest was completed is a rough guess.

Table 2. Number of days from nest completion to egg laying, hatching, and fledging for 11 nests.

|

|

Nest # |

Days to egg laying |

Days to hatch |

Days to Fledge* |

| 1 |

AMRO001 |

NA |

11.9 |

15.1 |

| 2 |

AMRO002 |

5.0 |

14.8 |

16.1 |

| 3 |

AMRO003 |

1.2 |

14.7 |

12.9 |

| 4 |

AMRO009 |

2.1 |

14.9 |

14.8 |

| 5 |

AMRO010 |

2.0 |

13.8 |

15.1 |

| 6 |

AMRO011 |

3.3 |

14.8 |

16.0 |

| 7 |

AMRO013 |

1.9 |

14.1 |

11.7 |

| 8 |

AMRO017 |

1.0 |

13.7 |

12.3 |

| 9 |

AMRO018 |

NA |

13.8 |

16.1 |

| 10 |

AMRO019 |

NA |

12.3 |

13.8 |

11 |

AMRO022 |

3.9 |

15.1 |

13.5 |

Average |

2.6 |

14.0 |

14.3 |

NA = data not available * All chicks fledged (nest empty)

There were occasions when one chick left the nest too early and was not able to fly into the woods. I watched an early fledgling taking shelter under a shrub close to the deck. It had the instinct to hide from view. The adults stayed nearby on alert and brought food. At the end of the day the chick hopped or flew to a safer location.

Nest Predation: Of the 25 American Robin nests in the Home 'patch', chicks fledged successfully from 20. Five nests were robbed of eggs in the nest. A few other nests were built in trees but not used at all, inferred from the absence of an adult sitting on the nest, and are not included in this study. No Brown-headed Cowbird eggs were found in any of the nests. American Robins have been reported to eject cowbird eggs soon after laying, and hence do not endure parasitism.

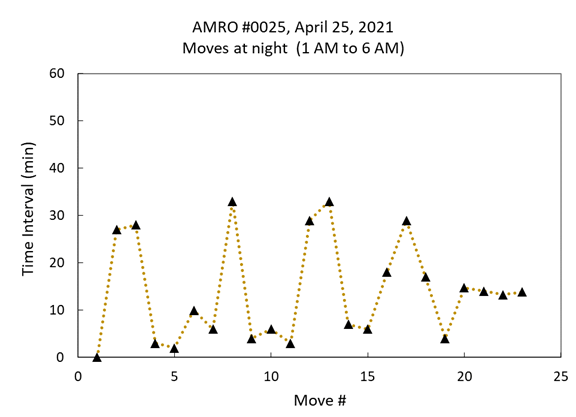

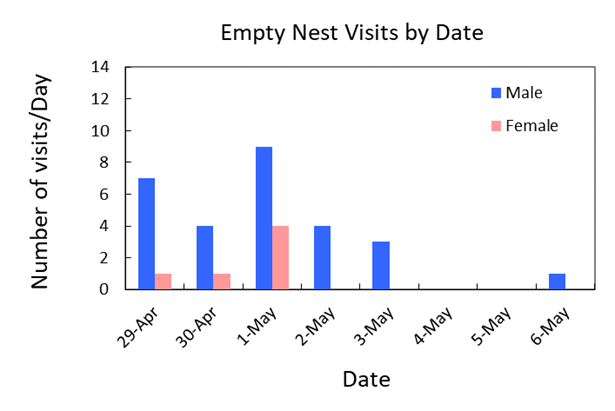

We assume that the adults abandon the nest after it is robbed, and the eggs go missing. The webcam gave us an insight into what happens after the nest is found empty. On April 25th, 2021, the nest (AMRO025) had four eggs. When I returned from a three-day vacation on April 28th, the nest was empty. I had turned the webcam off while away, so I do not know how the eggs disappeared. I turned the webcam on again and found that the robins were still visiting the nest. First both the male and female came to the nest. Sometimes the female sat on the nest as if to incubate but then left. After three days, only the male came to visit. The chart shows the number of visits per day by the male and the female.

The robins knew that the eggs were missing as no attempt was made to sit on the nest for any length of time. The female abandoned the nest visits, but why did the male continue to visit? Did they hope for the eggs to reappear? No attempt was made to start a second clutch. I did not find any nesting robins in the Home 'patch' the rest of the season. American Robins did not use this site in the following two years and instead chose to build nests on the support pole of a coral honeysuckle (Lonicera sempervirens) vine at the corner of my house.

Robins visiting the nest after losing all four eggs.

Nest Sanitation: The housekeeping of the nest was done by the male, removing any droppings from the nest. He came to the nest periodically and used his beak to clean the nest while perched on the rim. Once the chicks were a few days old they defecated over the rim, and he caught the fecal sac in mid-air (Day 10 photo) - quite a feat with coordination in ejecting and catching!! The empty nests were clean and there were no signs of any droppings or mites in the nest cup even after a month or two.

The female robin on a nest always flew away when someone approached the nest. She then watched from a nearby perch and chirped mildly protesting the intrusion. This is the behavior observed in general; robins are gentle birds, but there can be exceptions. Erica Backmann, who lives in Connecticut, reported an American Robin nesting in her yard with the male dive-bombing any person that came near the nest. She had to use an umbrella for protection as she walked towards her car. When I visited Erica, I was also attacked by this male robin; he was not discriminating. Others have reported American Robins reusing an old nest, a practice not observed in the 'patch'. We learned it is not fair to generalize the behavior of an avian species based on that of a small number of individuals.

This small bird, weighing less than an ounce, is one of the most vocal species here. The rufous back and lighter belly blend in well with dry shrubs and leaves. Its presence is most easily detected by loud vigorous singing heard all year round. Males and females look alike but can be differentiated when seen vocalizing as only the male sings. His repertoire may have over 20 song types comprising trills and rattles, each type repeated a few times. Nests are often close to human habitation, and they attempt two to three broods each year.

Carolina Wrens are regular visitors in the Home 'patch' all year, but it was only in 2023 that I had an opportunity to watch them nesting. On June 24th I heard several birds chattering in the woods. There was a family of Carolina Wrens hopping on a brush pile, adults and some recently fledged young with their gape flanges clearly visible. Next day, two adults were busily collecting nesting material from a planting bed and flying towards my house. They appeared to be preparing for another brood while some fledglings were still hanging around the adults. The nest location turned out to be under the lid of the 100-gallon propane

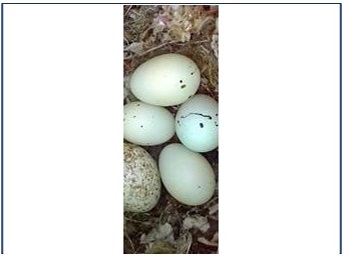

The nest was a loose collection of twigs, and there were five eggs in it - four lovely pink colored ones and a single larger speckled egg. Brown-headed Cowbird, a parasite brooder, had managed to find the nest in this well concealed location and laid an egg for the Carolina Wren to incubate.

Four Carolina Wren and one cowbird egg

Recently hatched chicks in the nest

It was best to let the mother bird sit on her eggs undisturbed. For the next two weeks I watched the male perched on a small tree nearby singing away. When a neighbor's cat came for a stroll along the planting bed, he was agitated and gave alarm calls - long chattering notes. On July 14th I saw both adults flying towards the nest with food in their beaks. It was time to check the nest again. I waited until I saw both adults on a nearby tree before lifting the lid. All eggs had hatched, but it was difficult to count the number of naked chicks without touching them, which I was not inclined to do.

I continued to watch the adults bringing food to the nest for the next four days. Then I was away from home for ten days. When I returned the male was singing in the woods but not seen. Under the lid was a mess of twigs and grass spread all over the tank top as if the little chicks wanted to spread out. I wondered if any of the chicks, Carolina Wrens and Brown-headed Cowbirds, had fledged successfully.

CarolinaWrens build nests in trees and shrubs but also select man-made objects. Some nest site locations listed in a 1948 study include shoes, mailboxes, old coat pockets and under covers of house propane tanks. My propane tank, installed to service a backup generator during power outages, has now been used as a nest box. I cleaned up the mess in case the birds return to use it again.

Chipping Sparrow, one of the smaller sparrows, has a rufous crown and an unstreaked breast. These sparrows arrive here in the beginning of April, announcing their presence with a series of loud trills repeated at intervals of about 10 seconds. Nest building begins in the middle of May - four to six weeks after arrival. Male and female look alike, but only the male sings in the breeding season, starting at dawn and continuing throughout the day. There are typically two broods in a season.

I have found many Chipping Sparrow nests in the yard over the years. Their favorite shrubs are sky pencil holly (Ilex crenata) in my front yard. I could see Chipping Sparrows going in and out of one of these shrubs from my office window. Finding the nest in the shrub was not easy as this small delicate object was neatly tucked away among the inner branches. They have also built nests in barberry (Berberis thunbergii) bushes, wisteria (Wisteria frutescens) vines and once in a 'Thundercloud' flowering plum (Prunus cerasifera) tree. Except for the nest in the plum tree, all other nests were just two to three feet from the ground.

I generally refrain from going near the nest site except once or twice when my curiosity takes over. When the female is incubating, the male sings from a perch higher up in a tree or on the roof. When I go near the nest the female flies away, but not too far, and chirps in protest. Once the eggs have hatched, both male and female bring food, making frequent trips between the tall trees in the woods and the nest. From the movements of the adults, I can guess if the eggs have hatched successfully.

Three eggs in a Chipping Sparrow nest

A Chipping Sparrow chick ready to fledge

The eggs, three to four in a clutch, are blue and lightly speckled. The nests are somewhat exposed and subject to parasite brooding by Brown-headed Cowbirds and predation. In July of 2007 and again in 2015, I watched a Chipping Sparrow bringing food to a cowbird chick. The chick was calling incessantly as it followed the sparrow. It was about three times the size of the sparrow who had to jump up from the ground to reach its open bill. It was touching to see how the instinct of parental care and protection is embedded in these creatures.

In 2023 two pairs of Chipping Sparrows nested in the yard at about the same time, one in the front yard and one in the backyard in a vine under the deck. As I looked through my window, I saw a Chipping Sparrow with nesting material in its beak flying towards the house and disappearing under the deck. Another one was on the dogwood (Cornus florida) tree about thirty feet from the deck. I located the nest, about three feet from the ground, while it was under construction in the hydrangea vine (Hydrangea anomala) climbing on the support pillars of the deck. The nest was completed in three days. On the fourth day, the Chipping Sparrow brought some white fluffy stuff to the nest. The following day I did not see these birds.

In the afternoon of May 7th, five days after the nest was initiated, there were two light blue eggs in the nest. A smartphone camera with a remote shutter, positioned a few inches above the nest with our team member Mark holding the branches apart, worked well for capturing an image. Next afternoon, we repeated the nest inspection at the same time of the day. To our surprise, there were four eggs, two blue and two larger speckled eggs. How did a Brown-headed Cowbird manage to lay two eggs in this nest in a twenty-four period? This had to be the work of two cowbirds as one bird lays only one egg per day. Did the Chipping Sparrow also lay another egg that day which the cowbirds removed?

The following day, there were five eggs in the nest, three of the Chipping Sparrow, and two of cowbirds. From then on, the female Chipping Sparrow was on the nest while the male perched on the dogwood tree delivered his trilled notes. On May 25th, 17 days after the incubation process began, I checked the nest again. There were no eggs in the nest, and the chicks were a few days old as their skins were covered with small down feathers. I could not tell exactly how many chicks were in the nest - at least four bills were visible. Two large mouths opened expecting food delivery from the camera positioned above.

Nest deep inside hydrangea vine

Two sparrow eggs

Three sparrow and two cowbird eggs

The vine had grown more, and the nest was now completely hidden behind dense foliage. I did not inspect the nest again but watched the Chipping Sparrows bringing food. They used the dogwood tree as an intermediate stop between the source of caterpillars on the tall trees and the nest. They were finding caterpillars, juicy green, flat brown, and knobby brown with a yellow tail, in less than three minutes. Then it was time to rest on the dogwood tree for a minute or two before the delivery. By May 29th they were bringing two to three caterpillars at a time keeping up with the demands of the cowbird chicks.

On the afternoon of May 31st, while I was watering plants, I saw a small chick in the planting bed. It was hopping awkwardly in between the shrubs. Then I heard the chip call of the Chipping Sparrows. The two of them were on the lower branches of trees at the edge of the woods, signaling to the chick to move towards the woods. I had enough time to get the camera before the chick disappeared in the woods. I checked the nest and found only one large chick remaining, clearly that of a cowbird. There was no sign of Chipping Sparrow chicks dead or alive. Three hours later the second chick fledged and landed near a boxwood shrub in the planting bed visible through my kitchen window. The Chipping Sparrows were nearby and kept calling but the chick hid under the shrub and did not venture out. The adults were focused on helping the fledgling they raised at the cost of losing their own. Next morning at 7AM, the second chick was still in the same shrub, and the sparrows were delivering green caterpillars. It took some more coaxing to get the chick to move away. I did not see this family with adopted chicks together again.

First cowbird fledgling on May 31st

Chipping Sparrow attending to second cowbird chick in shrub (June 1st)

While this drama was taking place in the backyard, another pair of Chipping Sparrows had a nest in a sky pencil holly in the front yard. The male would perch on the roof top and sing nonstop every time I stepped out on the driveway. When I examined the nest on May 31st, the day the cowbird chicks fledged in the backyard, this nest had one Chipping Sparrow egg, one cowbird egg and one recently hatched chick. On the next inspection, five days later, there were only chicks in the nest. I checked the nest again when the adults stopped bringing food and found it unoccupied. In the following two weeks I saw a Chipping Sparrow chick and a cowbird chick following a Chipping Sparrow in the woods.

Every year 20 to 30 Chipping Sparrows come to feed in the grassy areas of my backyard from September through early November, flocking before migrating south. There are juveniles, identified by a brown crown and thin dark streaks on the body, mixed with adults having rufous crowns. The presence of juveniles confirmed that some nests have been successful. A healthy population of Chipping Sparrows consistently returns each spring.

A House Finch is slightly smaller than a House Sparrow and is dichromatic. The male has red coloration on the crown, throat, upper back, and rump. The female is of dull tan-brown color with heavy streaking on the body. This species can survive in diverse habitats and is now widely distributed in most parts of North America. As the name implies, they often build nests on buildings and other man-made objects like lamps and planters. Nesting begins in late March or early April. It is one of the earliest songbird species to begin nesting and may have two to three broods in a season.

In the spring of 2020, a pair of House Finches chose to build a nest on top of a gutter spout near my front door. The female collected nesting material from various planting beds around the house, and the male followed her closely. Ten days after the nest building began, the female House Finch was sitting on the nest. A few days later the nest was left unattended, perhaps robbed by European Starlings or House Sparrows that were often on the roof of the house. I removed the nest debris from the gutter at the end of the season.

At about the same time in early spring of 2021, House Finches began building a nest at the same spot on the gutter. A couple of weeks later, the female was observed sitting on the nest at around 7 AM each morning for an hour or two. After four days she was on the nest all day long - incubation had begun. The male was perched on a tree next to the driveway and sang his warbled song ending with a downward slurred note. I learned more about his role when I walked out to photograph the female on the nest. His song ended abruptly, and he chirped twice; immediately the female flew away from the nest. I stayed fifty feet from the nest but was still considered a threat to his dear one.

Lawrence Slomer had introduced us to the borescope, an instrument designed to inspect hard to reach places, for inspecting nests. We acquired an Oiiwak Dual Lens Endoscope. Tying the 16 foot cable to a long rod and bending its end downwards, we raised it high enough to view the nest on the monitor and capture an image when the female was away from the nest. There were four eggs in the nest. A week later there was only one egg in the nest. The female continued to incubate for two more days and then abandoned it. All eggs were gone.

The same sequence was repeated in 2022. Nest building by the House Finches was initiated at the end of March, but they waited for a month to complete the nest, adding more material and rearranging the twigs. I viewed the nest from a safe distance at around 7 AM each morning - this being the time she sits on the nest to lay eggs, one each day. Egg laying began on April 26th. When I inspected the nest with the borescope on April 30th, there were five eggs in the nest. A Brown-headed Cowbird had laid an egg in the nest and the House Finch was incubating it along with four of her own. The next inspection on May 16th, two weeks later, revealed four chicks and one unhatched House Finch egg. Four days passed by, and then the House Finches were no longer around. The nest was empty - robbed again as in the previous year.

The resilient House Finches made one more attempt to use this nest site that season. In the middle of June, a pair was in the front yard quickly refurbishing the old nest. Three eggs were laid, but unfortunately on the fourth day the nest was on the ground and the eggs were missing.

I cleaned the nest area which is in full view of many birds in flight and also from the roof top. There were no attempts to use this site in 2023. Maybe the House Finches found a more secure place for nesting.

Female House Finch on nest

Four House Finch eggs

Four House Finch and one cowbird egg

The male Northern Cardinal has a striking brilliant red plumage. Throughout the breeding season his loud whistled songs are heard near forest edges and often even in city parks and gardens. The female has subdued tan coloration with a tinge of red on the wing and tail feathers. Her bright orange triangular bill and reddish crest matches that of the male. She also sings when nesting. There are typically two broods in a season, the male actively guarding his territory while the female builds the nest and incubates. Both parents feed the nestlings, while the male also performs guard duty throughout.

In previous years, I had seen fledglings being attended to by the parents but did not find any nests. In 2023, I luckily located two nests, one in May and the second one in August, likely of the same pair. The first nest was in a burning bush (Euonymus alatus) next to my neighbor's house. As the female was collecting nesting material and taking it to the nest site, the male followed her closely. I could guess the progress on the nest only by watching the movement of the adults. When the female was incubating, the male stood guard and sang from dawn to dusk perched on different trees in the area. After a couple of weeks, both parents were making frequent trips to the nest, bringing food to the chicks. Then on May 13th, when I went out to water some shrubs, I saw the cardinals calling and moving between the nesting site and the woods. I saw some movement on a small shrub in the planting bed and spotted a fledgling as it hopped awkwardly from one branch to another. I dropped the watering can and ran inside to get a camera. The chick was still on the same plant when I returned. Satisfied with a few nice photographs I moved away and watched the parents urging this chick and another one I could not see to move towards the woods. They succeeded in getting the chicks to a safe place, and I did not see them again. For the next week to ten days the male cardinal was often at the edge of the woods, moving from one tree to another. When the neighbor's cat came for a stroll, he gave chip alarm calls, keeping the cat in sight until she left the area.

In the beginning of August, I was cutting some black cherry (Prunus serotina) tree branches that were extending horizontally and getting tangled with the dogwood tree. After snipping a few I noticed a nest on the next branch I was about to cut. Not knowing for sure if this was a nest in use or an abandoned one, I left it alone and stopped trimming. Next day, looking through my window, I saw a female cardinal moving in that area. Just by sheer chance, through a small gap in the leaves I saw her sitting in the nest. Now I could follow the activity on the nest from inside my house, 50 feet away. When on the nest she was well camouflaged except for her orange beak shining through the leaves as she moved. To check the status of the nest, I got help from our team member Mark who volunteered to climb a ladder and take pictures with a smartphone camera. There were two eggs in the nest. After an interval of two weeks, we checked the nest again, and there were two chicks with beaks wide open, expecting to receive food. From then on, I watched the adults through my window as they went towards the nest to feed the chicks. One morning 10 to 12 days after the eggs hatched, there was a high level of activity with the adult cardinals going back and forth to the nest area, and then all was quiet. For another week, the male cardinal was in the woods and sounding alerts when the cat came by, so I assume the chicks fledged successfully. He stopped singing altogether once the nest was empty and made chip calls only.

There were a couple of heavy rainstorms with high winds during the nesting period. The nest was anchored so securely to the branch with a thicker twig (indicated by an arrow in the photograph) that it could withstand severe weather - a noteworthy engineering feat by the female cardinal. The empty nest after fledging was intact and clean.

Northern Cardinal nest anchored to a branch

Two eggs in the nest

Two hungry chicks

Red-tailed Hawk

A common large hawk in this area, the Red-tailed Hawk is often seen perched on power lines and trees along highways and roads. Adults are distinguished from other hawk species by reddish tail feathers and a dark band on the chest. Juveniles have gray tail feathers barred with darker gray. This hawk preys on small mammals, snakes, rodents, and bats. Pigeons and doves are also part of the diet, but typically small songbirds are spared. American Robins, Tufted Titmice and other songbirds often perch comfortably near a Red-tailed Hawk on a tree after the breeding season.

In 1999, 2000 and 2001, Red-tailed Hawks nested in the woods behind my house. The nest was not well visible from the house, but I could see the hawks flying to and from the nest location. In early July, two young hawks were learning to fly, hopping from branch to branch, then sitting still after each maneuver to gain confidence. Their presence was easily detected by the alarm calls of robins and other songbirds busily harassing these young hawks by dive bombing.

Eighteen years later, in April 2019, I located a Red-tailed Hawk nest in the woods behind my house. One adult was sitting on the nest, another alarmed by my presence was circling above and calling. By mid-May, two fluffy white chicks were visible above the rim of the nest which was about 25 feet above ground. I did not see fully grown chicks before fledging as I was away for the first half of June. The nest was abandoned when I returned. Juvenile hawks were calling in July and August, confirming that the nesting was successful.

Red-tailed Hawk nest

One fluffy hawk chick in 2019

By the spring of 2020, the old nest had fallen apart, and the hawks built a new nest on the north side of a nearby hill in the back woods. The nest was visible from the top of the hill at a distance of 100 feet. I climbed the hill to check the nest once a week or so and took photographs with a Nikon Coolpix 900 camera with 80X zoom. Two fluffy white chicks in the nests were visible in the nest by May 3rd. The chicks grew to adult size, and the nest was empty by the middle of June. On July 8th a juvenile Red-tailed Hawk was perched on a tree and moving awkwardly. Later as in the previous year, juvenile hawks were often circling overhead and calling for hours at a time in the summer.

One hawk chick with open beak in 2020

Juvenile Red-tailed Hawk

In the winter of 2020 -2021, a pair of Red-tailed Hawks was often seen perched together in the woods for an hour or more at a time. As is apparent from this photograph of the pair, the female was slightly larger than the male. She had a darker reddish head and could be easily distinguished from the male even when perched alone. By mid-March, her brood patch, a bald area on the belly for incubation, was visible, indicating the presence of a nest nearby. I searched the woods and tried to follow the flight trajectories of the hawks leading to the nest but failed to locate it. Sections of the woods extend along the neighboring backyards and are not accessible, limiting the search area.

In 2022 and 2023 Red-tailed Hawks have not nested in the vicinity of the 'patch'.

The smallest of the small birds in the northeastern USA, the Ruby-throated Hummingbird is named after the ruby-red throat of the male. This species is dichromatic; the female has a white throat and a black and white tipped tail. She shares the iridescent green of the wing feathers with the male. Migrating north from wintering grounds in Central America, these hummingbirds are in this area from May until late September. Even though I do not have a hummingbird feeder loaded with sugar water, these birds are in my yard drinking nectar from different blossoms all through the season.

The male hummingbird arrives from the south in early May, consuming nectar from early blooming plants. Unlike other songbirds in the 'patch', nest building, incubation and caring for the young is done by the female alone while the male is elsewhere drinking nectar and having territorial battles near feeders. I often wondered if there was a nest nearby as I see only females, one or more, from June through September. Just by sheer chance, in June of 2022 the flight path of a female led me to her nest under construction. The nest was about 50 feet above ground on a small branch of a tall tree at the corner of my backyard. The nest of this small bird is even smaller than the bird itself, the outside diameter and height are both less than one and a half inches. With a spotting scope (Nikon Monarch Fieldscope 82 ED) placed on a tripod next to my bedroom window, I could get a good view of the nest from dawn to dusk even when it was raining. For taking photographs and videos in good weather, I used a Nikon Coolpix camera with 80X zoom, mounted on a tripod on the deck. The nature movie Watching a Ruby-throated Hummingbird's Nest on this website includes an introduction to Ruby-throated Hummingbirds and follows the activities of this nest in my backyard.

Location of hummingbird nest (inside red circle)

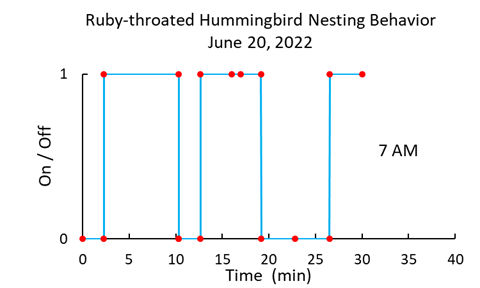

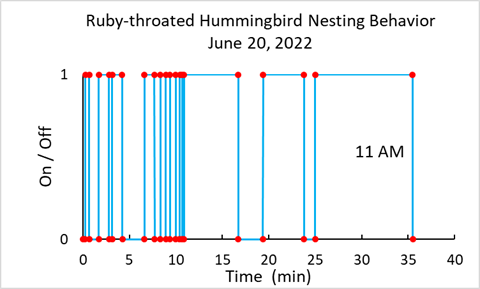

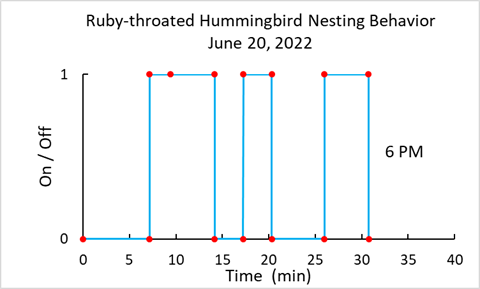

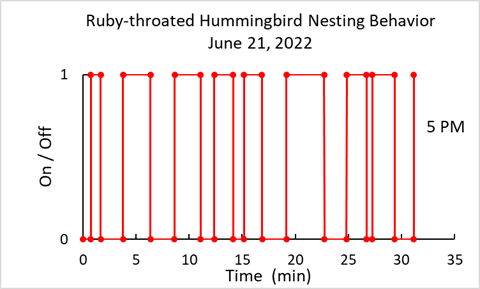

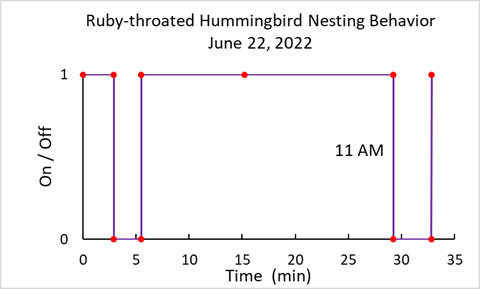

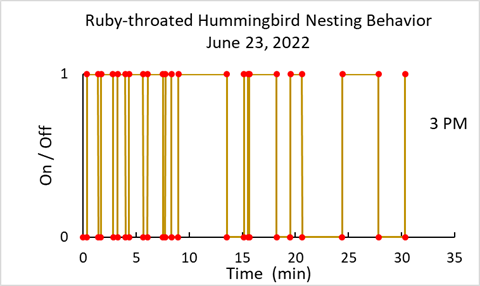

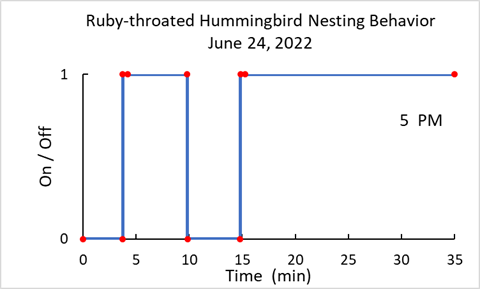

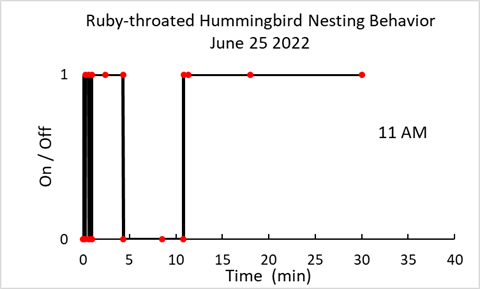

On June 8th, the day I located the nest, the hummingbird made many trips to the nest but did not sit on it. Next day onwards, from June 9th through June 21st, she was on and off the nest. Sometimes she took her place on the nest right away and sat still. Other times, she returned quickly and padded the outside wall of the nest with her beak. I named this process touching up (TU) and began recording the time on and off the nest in 30 minute intervals at different times of the day. The plots below show the data collected on June 20th at 7 AM, 11 AM and 6 PM. At 7 AM and at 6 PM, she was on the nest for three to seven minutes and away for about the same time. At 11 AM, she made many short trips, each lasting about one minute while she performed TUs. After eight such trips, she settled down to the routine of spending five minutes or so on the nest. Observations recorded on June 21st, June 22nd and June 23rd are also shown. On June 22nd, she was on the nest for 22 minutes which was unusual. She also changed her position on the nest, facing towards east, west, north, or south.

Sometimes I could see the mother hummingbird opening and closing her beak while sitting on the nest, as if she were singing lullabies or talking to the embryos in the eggs - telling them about the world they would see after fledging.

The observed behavior of this hummingbird during incubation was significantly different from other songbirds who spend most of the time sitting on the eggs. Between June 9th and June 21st, the average maximum and minimum temperatures were 78 oF and 55 oF respectively. The required temperature for incubation is ~ 100 oF, much higher than the ambient temperature during this period. Hummingbirds construct their nest with plant-down and spider webbing, not grass and twigs. Perhaps it is insulated well enough that she can be away for longer periods.

Hummingbird on nest for incubation

Touching up the nest

At 5 AM on June 24th, the mother hummingbird was outside the nest and used her beak to remove some material from inside and then settled down in the typical incubating position. At 2:45 PM, when she returned to the nest, she perched outside and put her beak inside before settling down on the nest. The same behavior was repeated at 5:30 PM during the 30 minute observation period. Then she sat on the nest for over 20 minutes. It appeared that the eggs had hatched. I do not know if the eggs hatched on the same day or if one egg hatched earlier (perhaps on June 22nd). From then on, she was on the nest for over 20 minutes and away for five to seven minutes. When she returned to the nest, she shook and bounced for a few seconds. This was the brooding stage when the chicks have bare skin and need to be kept warm.

On June 28th the tip of one small beak of a chick was visible above the rim of the nest when the mother brought food. On June 30th a small head was visible, and there was evidence of the mother feeding a second chick in the nest. By July 1st, eight days after hatching, the mother stopped brooding. Now she was away most of the time except when the sun was directly on the nest in the afternoon. For about an hour or so, she sat on the nest with her tail feathers spread out to shade the chicks.

The two chicks were growing fast, their heads and beaks visible over the rim after 12 days of growth. I watched one chick defecate over the rim - had to do it right as there was no adult to catch it. The chicks began exercising their wings, flapping and fluttering several times during the day. Their feathers had grown, and they did not need protection from the sun. The mother was not drinking nectar from the nearby blossoms. She would fly away and return with a meal. I could not tell if the meal was an insect or nectar.

A few days before fledging, the two chicks appeared to be of the same size. The nest was too small to fully accommodate both, and their beaks and tails were sticking outside the nest wall. Then on the morning of July 15th, one chick was perched on the rim. At 8:09 AM it flew away. The second chick remained in the nest for another 45 minutes. Then it too left the nest.

Day 7 after hatching

Day 15

Day 22 (ready to fledge)

There was no male on guard duty, yet the nest remained safe. I saw an American Robin land below the nest on a different branch, and it stayed for a few seconds. Later a Chipping Sparrow landed on a branch above the nest and stayed briefly. The mother hummingbird was not agitated by these birds perched so close to her nest. One morning a White-breasted Nuthatch approached the nest but chose not to get too close. A Blue Jay came close as I watched and held my breath praying no harm would come to the dainty nestlings. This big bird, known to eat eggs and chicks, paid no attention to the nest.

The delicate hummingbird nest disintegrated in the next couple of months. In 2023, spongy moths (Lymantria dispar) devoured the leaves of the tree in which the hummingbird had nested the previous year and those of many other tall trees in my woods. I did see two to three female hummingbirds flying together or drinking nectar from the same plant in August and September. These appeared to be juveniles following an adult - perhaps there was a nest nearby.

Concluding Remarks

The internal clock of birds brings about physiological and hormone level changes in preparation for breeding as the day length increases in this temperate zone. The breeding period may be genetically programmed, but for successful reproduction there are many day-to-day decisions to be made by individuals. Selecting a nest site, constructing a secure nest with available materials, and incubating under varying ambient conditions are tasks performed primarily by the female with some assistance from her male partner. We saw evidence of American Robin discarding her first nest building attempt and learning from this exercise. The female Northern Cardinal devised ways to securely anchor her nest on a thin branch. The Ruby-throated Hummingbird knew when to shade the nestlings from the sun and when it was safe to be away from the nest. Keeping all the eggs in a clutch uniformly warm in a cup nest exposed to freezing temperatures required vigilance at all hours of day and night.

The nestlings are born naked and need both thermal protection and food for the first few days. Their demand for food increases as they grow. The parents must find food sources close to the nest to make deliveries every few minutes. Not all nestlings are fed each time adults return to the nest with food. Somehow the adults coordinate the deliveries and ensure that all nestlings are adequately fed and that they themselves remain in good physical condition. Robin chicks fledge successfully on a diet of earthworms and caterpillars for the first brood or on a mixed diet of insects and berries for the second and third broods. There is no need for calorie counts, food value estimates, diet control programs, and medical intervention for growth for the chicks and weight control for adults. Nature has equipped all these creatures with a sense of what and when to eat.

Nests are subject to predation, parasitism, and exposure to severe weather. American Robins, Carolina Wrens, Chipping Sparrows, and Northern Cardinals attempt two to three broods in a season. Ruby-throated Hummingbirds may attempt a second nest only if the first nest fails. Red-tailed Hawks have a longer nesting season and can only have one brood. Somehow, a healthy population of these seven species and of the Brown-headed Cowbirds is maintained in the Home 'patch'. They have adapted well to the environment in close proximity to human habitation.

AAP Appilcation

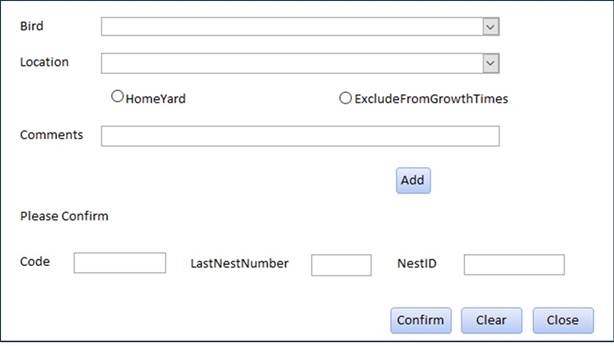

Our AAP Application developed by Hemant Sogani includes a tab for recording nesting observations in any location. Each nest is given an identification tag (ID) in the NestMaster form shown in Fig. A1. Once a species and the location of the nest entries are made, the nest ID is automatically generated, incrementing it by one digit from the previous nest ID of the same species. The nest ID begins with the four-letter code for the bird species followed by sequential digits. As an example, AMRO026 is an American Robin nest # 26.

Fig. A1 NestMaster form

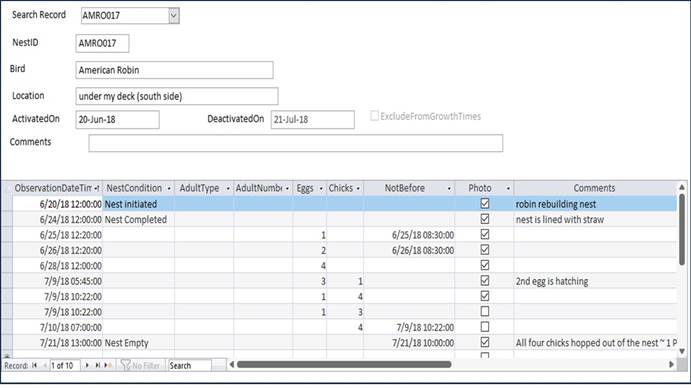

Nesting activities are recorded in the NestingDetails form. All the records of a nest are viewed in a single table. An example table for nest AMRO017 is shown in Fig. A2. The nest built under my deck was initiated on June 20, 2018, and completed in four days. The first egg was laid on June 25th, and the fourth egg on June 28th. The eggs hatched between July 9th and July 10th. All four chicks fledged together on July 21st. There is a checkmark for relevant photographs (hyperlink may be added) and comments are included.

Fig. A2 Nesting details for American Robin nest # AMRO017

As nests are not observed continuously, each entry has an observation time (ObservationTime) and a previous observation time (NotBefore). Hence, an event on record occurred sometime between the NotBefore and ObservationTime. In AMRO017 the first egg was laid on June 25th between 8:30 AM and 12:20 PM.

For nests having the date and time of egg laying, hatching, and fledging available, the time interval to hatch and fledge are calculated in the GrowthTime table (Table 2). Such data are only available for American Robins because the nests under the deck could be observed regularly.

New York State Breeding Bird Atlas

A Breeding Bird Atlas (BBA) serves as a tool for monitoring the breeding status of avian species in a specific area. The first such atlas for New York State was compiled in 1980-1985, and the second twenty years later (2000-2005). Work on the third BBA began in 2020 and will end in 2024. For this survey the entire state is divided into 3 mile x 3 mile square blocks. The survey for the Hopewell Junction_NW block which includes the Home 'patch' was completed in 2020.

NY State BBA has established Breeding Codes for entering observations in the eBird BBA portal managed by Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Definite evidence of breeding requires one of observation types in the 'confirmed' category. With contributions from 31 Atlasers, a total of 55 species were 'confirmed' breeding in Hopewell Junction_NW block as of December 2023. A breakdown of the number of 'confirmed' species for each code is given in Table A1. Note that nests with young were observed for only seven of the 55 species. These species are listed in Table A2.

THe Home 'patch' covers an area of ~ 0.02 square miles, 1/450th of the area of the Atlas block. During the 2020-2023 period, I observed nests with eggs or young of seven species in the Home 'patch' as described in this document. Five of these species are not listed in Table A2. Although I entered the data in eBird, some entries were not apparently picked up by the NY BBA portal of eBird. A total of 30 species were 'confirmed' breeding in the Home 'patch'. Of these, 19 species are here all year and 11 are migrants. A complete list of the 'confirmed' species in the 'patch' is given in Table A3.

Table A1

Number of 'confirmed' species and Breeding Codes in Atlas block Hopewell Junction _NW and the Home 'patch'

Status |

Breeding Code |

Hopewell Junction_NW # of species |

The Home 'patch' # of species |

Total 'confirmed' |

- |

55 |

30 |

Nest with young |

NY |

7 |

7 |

Nest with Eggs |

NE |

- |

- |

Nest Building |

NB |

5 |

- |

Feeding Young |

FY |

17 |

8 |

Fledglings |

FL |

16 |

6 |

Carrying Nesting Material |

CN |

7 |

7 |

Carrying Fecal Sac |

CF |

2 |

3 |

Physiological Evidence |

PE |

1 |

- |

Table A2

Number of reports of 'Nest with Young' (breeding code NY) in Atlas block Hopewell Junction _NW

# of nests |

Species |

7 |

Red-bellied Woodpecker |

3 |

Black-capped Chickadee |

6 |

Tree Swallow |

5 |

House Wren |

2 |

Carolina Wren |

4 |

Eastern Bluebird |

1 |

American Robin |

Collecting accurate information on the number of species as well as the abundance of a species successfully breeding in a large area is a monumental task. The BBA project, with the participation of experts and amateurs, attempts to survey and gather a representative dataset. As the bird species populations decline over time, there is an increase in the number of participants (community scientists). Ease of entering data in eBird and assistance in bird identification using the Merlin App provided by Cornell Lab of Ornithology have made data collection much more efficient than forty years ago when the first BBA was conducted in New York State. Deconvolving these factors gets to be very complicated. However, awareness and interest go a long way in wildlife conservation efforts - all for the good.

Table A3

List of species 'confirmed' breeding in the Home 'patch' in 2020 - 2023.

nbsp |

Species |

Breeding Code |

Description |

Resident Term |

1 |

American Robin |

NY |

Nest with young |

A |

2 |

Carolina Wren |

NY |

Nest with young |

A |

3 |

Chipping Sparrow |

NY |

Nest with young |

S |

4 |

Northern Cardinal |

NY |

Nest with young |

A |

5 |

Red-tailed Hawk |

NY |

Nest with young |

A |

6 |

Ruby-throated Hummingbird |

NY |

Nest with young |

S |

7 |

House Finch |

NY |

Nest with young |

A |

8 |

American Goldfinch |

FY |

Feeding young |

A |

9 |

Baltimore Oriole |

FY |

Feeding young |

S |

10 |

Barn Swallow |

FY |

Feeding young |

S |

11 |

Downy Woodpecker |

FY |

Feeding young |

A |

12 |

Eastern Bluebird |

FY |

Feeding young |

A |

13 |

Northern Flicker |

FY |

Feeding young |

A |

14 |

Northern Mockingbird |

FY |

Feeding young |

A |

15 |

Song Sparrow |

FY |

Feeding young |

A |

16 |

Canada Goose |

FY |

Recently fledged young |

A |

17 |

Eastern Wood-Pewee |

FY |

Recently fledged young |

S |

18 |

European Starling |

FY |

Recently fledged young |

A |

19 |

Red-bellied Woodpecker |

FY |

Recently fledged young |

A |

20 |

Tufted Titmouse |

FY |

Recently fledged young |

A |

21 |

White-breasted Nuthatch |

FY |

Recently fledged young |

A |

22 |

American Crow |

FY |

Carrying nesting material |

A |

23 |

Blue Jay |

CN |

Carrying nesting material |

A |

24 |

Gray Catbird |

CN |

Carrying nesting material |

S |

25 |

Great Crested Flycatcher |

CN |

Carrying nesting material |

S |

26 |

Mourning Dove |

CN |

Carrying nesting material |

A |

27 |

Scarlet Tanager |

CN |

Carrying nesting material |

S |

28 |

House Wren |

CF |

Carrying food |

S |

29 |

Red-eyed Vireo |

CF |

Carrying food |

S |

30 |

Yellow Warbler |

CF |

Carrying food |

S |

⁎ A = All year S = Summer migrants

Acknowledgments

We thank Lawrence Slomer for recommending various instruments for imaging bird nests and Sue Ouellette for reading the manuscript and providing numerous editorial comments.

1. Birds of the World, Cornell Lab of Ornithology and references cited therein.

2. Eastern Birds' Nests: Peterson Field Guides. Houghton Mufflin Company, 1975

3. Handbook of Bird Biology, 3rd Edition. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, 2016